Rafting lumber down the Connecticut

River was a common economic activity in the late 18th

century. The forests in Southern New England were becoming depleted,

so increasing numbers of entrepreneurs in Northern New England took

advantage of the burgeoning lumber market, cutting trees and shipping

them down the river to be processed in sawmills downstream. The first

real lumber baron on the Connecticut River was David Sumner of

Hartland.

David Sumner was born into a fairly

wealthy Claremont, New Hampshire family in 1776. His father was

determined that he would graduate from college, but David was more

interested in business than in academics. As a young adult, he

trained in the mercantile business at Lyman's Store in White River

Junction, then established his own store in Hartland.

In 1805, David married Martha Brandon

Foxcroft, the daughter of a doctor in Brookfield, Masschusetts. He

became an important person in Hartland. He was elected captain of the

Hartland militia in the War of 1812, was a state legislator, justice

of the peace, and Hartland's postmaster for 20 years. Often a

storekeeper would be the postmaster, as the store was the logical

place to have a post office. David became quite wealthy from these

various ventures, and he also inherited an estate from his father.

In colonial New Hampshire, Governor

Wentworth set aside 500 acres for himself in each township. These

tracts of land were called “The Governor's Rights”. David's

father, Benjamin Sumner, had purchased the Claremont tract from the

Governor, and David inherited that land from him when he died. In

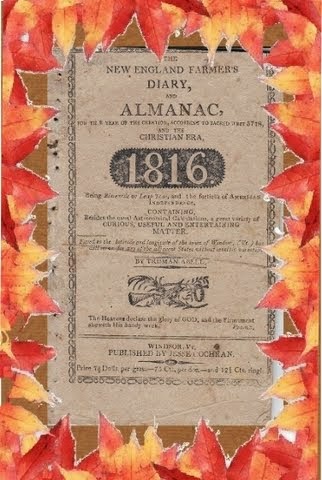

1816, David purchased several more “Governor's Rights” tracts

from Governor Wentworth's widow. These tracts were in northern

Vermont and New Hampshire, and contained huge quantities of lumber.

With these land acquisitions, David

Sumner entered the lumber business. He employed crews of lumbermen to

cut wood in the north country, then raft it down the Connecticut

River. There were three canal and lock systems on the Connecticut

River, at Wilder, Hartland, and Bellows Falls. Perez Gallup owned the

canal and locks at Hartland, but when he died, Sumner bought the

property from his estate, improved the canal and locks, and built a

sawmill there. He built a second sawmill in Dalton, New Hampshire,

which was run by his nephew. His fortune increasing by leaps and

bounds, he built a mansion for himself and his wife, which is still

standing in Hartland, and is now a Bed and Breakfast Inn.

In 1825, David Sumner's crews moved

two million board feet of lumber from the Johns River in Dalton, New

Hampshire to the mill at Hartland. That year, many of the logs were

mast logs, which were still very valuable. Although they were more

valuable, mast logs were so long and big that they often caused log

jams. One of these log jams took 15 to 20 men a full day to pick

apart, costing Sumner $8. That same year, thieves in Haverhill and

Orford stole some of the logs.

Most of Sumner's logs were sent loose

down the Connecticut River to Hartland, but often at Hartland, some

were grouped into rafts and sent further South to be sawn into lumber

under a contract. These rafts were piled high with shingles, potash

and other wood products, destined for the Southern New England

market. In 1832 a raft of three boxes of three boxes contained 26,614

board feet of lumber and shingles, headed down the Connecticut.

These huge boxes had to be dismantled

to go through canals and over falls, and if the river was low it made

things much harder for the crew. In 1824, the combination of low

water and huge logs caused log jams at Millers Falls and Hadley

Falls, Massachusetts, and the crew had to use crews of hired oxen

working from the riverbank to break the jam. This was the heavy

equipment available in that day. During this process, one man was

drowned.

Driving logs downriver was dangerous

work, especially in jams. The men actually “rode the logs”, even

while trying to untangle a log jam. A sudden shift in logs could mean

that a log driver would lose his footing and fall into the river.

Many men who went for an impromptu swim simply made for the river's

edge and emerged unharmed. Some, however, were overtaken by the

current and swept downstream. Worse, a leg or arm could get pinned or

crushed in a log jam, and a badly injured person can hardly swim to

shore in fast current.

It was unusual for the drivers to make

it all the way to Southern Massachusetts or Connecticut without

encountering some type of difficulty. In 1824, they arrived at South

Hadley Falls with 28 rafts loaded with wood products. It was Sunday,

and neither the canal crews nor the Sumner crews would work. Finally,

with enough extra money and persuasion, the crews went into action

and the logs successfully went over the falls and the other products

were safely transported through the locks.

Southworth Park has picnic tables and a parking lot, and it is a trailhead for one of the Rivendell Trails. On the right side of the parking lot, there is an opening in the brush that leads to a meadow. There is a nice view from the hilltop. One of the West Fairlee portions of the Rivendell Trail begins on the left of the parking lot. This part of the Rivendell Trail is somewhat difficult, although I am fifty and have a bad left foot and I am more than capable of hiking it. Some of it is steep, and this trail involves climbing over and around some rocks, streams, and one uprooted tree. This trail leads over to Blood Brook Road in West Fairlee Center. There is a stone wall about halfway between Southworth Park and Blood Brook Road. From the park to the stone wall, the trail is very well marked, after the stone wall, the path and markings are less clear.

Southworth Park has picnic tables and a parking lot, and it is a trailhead for one of the Rivendell Trails. On the right side of the parking lot, there is an opening in the brush that leads to a meadow. There is a nice view from the hilltop. One of the West Fairlee portions of the Rivendell Trail begins on the left of the parking lot. This part of the Rivendell Trail is somewhat difficult, although I am fifty and have a bad left foot and I am more than capable of hiking it. Some of it is steep, and this trail involves climbing over and around some rocks, streams, and one uprooted tree. This trail leads over to Blood Brook Road in West Fairlee Center. There is a stone wall about halfway between Southworth Park and Blood Brook Road. From the park to the stone wall, the trail is very well marked, after the stone wall, the path and markings are less clear.