Lots of research in the Barnard town

office has yielded some new information about the Aikens family.

Property transfer records from 1862 show that while Charles was off

to war, Jane signed a 5 year lease on a house across from the town

common. She would share half of the house with another family, but

she had an option to buy at the end of the five years. The town

common was right by the current school, where the graveyard is now.

There is a house at this location now, but I researched the deed to

that house, and if it is the house Jane leased for five years in

1962, she and Charles did not buy it at the end of the war, because I

researched all the way back to 1868, and their names didn't pop up.

Charles and Jane did a lot of buying

and selling property in Barnard throughout the years, often in only

Jane's name. I also found it interesting that Charles' last property

transfer was at the end of his life, after Jane died, when he signed

his house over to their son Seth, was signed with “his mark”

rather than his signature. It is possible that he was too weak to

sign his name, but also possible that he never learned to write.

This might explain why so many property transfers over the years took

place in Jane's name. She could sign her signature, at least.

I never cease to be surprised at how

mobile people were in the mid 19th century. Some people

moved all over the country, and even if , like the Aikens family,

they stayed in one town, they often lived in three or four houses

over the course of their lives, and that was what Charles and Jane

Aikens did. I think people had less stuff, and this made it easier

to move from house to house. I also think they didn't have as much

debt with their mortgages, so it was easier financially to switch

houses.

Charles and Jane's son, Seth

Billington Aikens, was named after his uncle, Seth Billington of

Jersey City, New Jersey. Seth Billington's name is also on a

property transfer a little bit later on. He bought Charles'

blacksmith shop. My guess is that Charles and Jane were strapped for

cash at some point, and he bought the shop to help them out. Seth

Billington owned a soap factory in New Jersey. His wife was Jane's

sister.

Seth was born in 1865, the year the

Civil War ended. His father was not home for his birth, but met his

son the baby was a few months old, when he returned from war. Seth

was Charles and Jane's only child. They had a stillborn son and a

little girl who died from scald burns when she was a few months more

than a year old.

Seth married Alice Wright, who also

grew up in Barnard. They had three children: Frances, born in 1892;

Forrest, born in 1895, and Charles, born in 1901. Charles died in

1918, and Jane died in 1911, so the boys would have grown up knowing

their grandparents. I also researched property transfers for Seth

and Alice, and found the deed to their first house, which was in the

neighborhood between the library and the schoolhouse (now the

historical society.

Barnard town reports from the late

1800's indicate that there were 10 schoolhouses in Barnard. In 1901,

Forest was six and would have started school that year, because there

was no such thing as kindergarten. That year, eight or nine

schoolhouses had a teacher. Bessie Meacham taught in South Barnard,

Lucy Hammond taught in East Barnard, Jenny Cooty taught at the Upper

Village school, Mae Savage taught in the North End, Inez Ellis taught

at the Gambell School, Blanche Sewall taught at the Wright School,

Mabel Dyke taught on Lillie Hill, Leona Adams taught at the Morgan

School, and Albert Eastman, the only male teacher, taught at Turkey

Hollow.

Schools in Vermont at the turn of the

century had three terms, Fall, Winter and Spring, of 10 weeks each.

There was a day or two off for Thanksgiving, and a winter break in

December, ending the Fall term, a winter break in February ending the

Winter term, and no April vacation, but school ended earlier.

Teachers were hired for each term, and

often a school would go through two or three teachers in a year.

Contrary to popular belief, students in those days were not

necessarily well-behaved, and the young inexperienced teachers often

had a hard time controlling the students. Teachers did board with

local families, and the town paid their board. They would stay with

one family for a term, and usually continued on with that family

during the terms of that school year, if they continued to teach.

The town paid the families for the teachers' board, and that expense

was noted in town report.

The town report records that Barnard

paid $95.00 for wood to heat the schoolhouses. Based on entries in

the town reports that specified amount paid for number of cords, it

appears that the town of Barnard paid about $4.00 a cord for wood.

Adjusted for inflation, that would be $183 a cord in today's money.

This is a pretty good bargain compared to today's wood prices. We

have no way of knowing, however, if this was the going rate for

firewood, or if townspeople sold the town wood at a discounted price

so the kids would be warm. The $95 Barnard paid in 1901, divided by

$4 equals 24, rounded up. This is about 2 cords per schoolhouse,

which doesn't seem like enough to me. I have no doubt that those

schoolrooms weren't warm in the winter, but even so, two cords a year

is not enough to heat schoolhouses that were not insulated, using

inefficient stoves, in the dead of winter in Vermont. So, either the

town bought wood that was not documented, or families donated wood,

or both.

Barnard paid a guy to start the fires

in each school. Historical literature often shows the teacher being

responsible for starting the fires, but this was not the case in

Barnard. It is possible that these males were students. The town

also paid a different person for janitorial work. I'm quite sure

that these were students, since Forrest Aikens was paid $3.50 for

janitorial work in February of 1905 in School No. 1, when he was 10

years old, and each year after that until he went to high school.

Again in literature, you always read about the boys starting the

fires and doing the janitorial work at the schools, but at least in

Barnard, they were paid.

In many ways, reading the reports

regarding education in the Town of Barnard and the State of Vermont

in 1901 is an exercise in the old adage “The More Things Change,

the More They Stay the Same”. In 1896, the school superintendent

states that “The attendance and work done in some of the schools

was highly satisfactory, in others, not quite up to the high

standards we had hoped to attain.”

I was surprised that Barnard had a

school superintendent. The late 18 and early 1900's was an era of

rapid change for Vermont schools. In 1845, Vermont elected its first

State Superintendent of Education, a precursor of today's Department

of Ed. In 1870, state legislature passed a law “allowing” towns

to consolidate their schools into town-wide school systems but only

40 towns did this, and 15 abandoned the experiment, returning to the

district system. In 1892, the Vermont legislature outlawed the

school district system and mandated that every town in Vermont manage

education on a school system basis, with every system having a

superintendent.

Rural towns like Barnard still

insisted on maintaining local control of their many schools. In

1902, the town voted to purchase globes and schoolbooks for each of

the schools. The superintendent's report for that year states that

“There is a reasonable degree of interest manifest by the pupils,

and regular attendance. There is, however, a lack of interest in the

schools on the part of the parents. They don't feel the interest in

schools that they ought to.” Back then, as today, parents were

struggling to feed, clothe, and shelter their children, and did a

good job getting them up and to school, but in many cases, this task

taxed their resources and there wasn't a lot left over for

involvement in other ways.

In 1903, there is a new expense listed

for the South Barnard School – a telephone bill. In 1905, the

superintendent's report mentions that the Barnard Schools had

improved instruction in at least one area of the curriculum. “That

part of our general laws that prescribe that all pupils shall be

thoroughly instructed in elementary physiology and hygiene with

special reference to the effect of alcoholic drinks and narcotics on

the human system is being more thoroughly complied with than in

former years. That is a step in the right direction.” Health

class, anyone? And it is jarring to read about narcotics in 1903. In

Barnard.

Two new expenses were added to the

school budget in 1907. That year, Barnard began paying tuition to

Woodstock, Bethel and Montpelier for its students to attend high

schools in those towns. The town also paid huge transportation bills

to get those students to their respective schools. The transportation

expenses for high school students totaled $186.10 for one year. I

hesitate to draw any conclusions about that figure, though. Was it a

more accurate reflection of the expenses incurred transporting

students than the expenses listed for firewood, or did some parents

volunteer to transport students to high school, making the actual

total even higher? It's fair to say that Barnard paid a significant

sum of money to transport high school students, in any case.

Although the mandatory creation of

school systems was a step toward school consolidation, small hill

towns all over Vermont really balked at the idea of sending all their

students to one localized school. Part of that centered around

losing the schools children had attended for decades, but part of it

was a concern about transporting children over poor roads in winter,

and the fact that farm families needed their children home in time to

do afternoon chores, and sometimes even needed them home before

school for morning chores. This was possible when students walked to

schools that were close to their homes, but more difficult when they

had to be transported to schools miles away. In the bigger towns,

school systems had begun consolidating schools in the late 1800's,

but the hill villages fought this trend.

Of course, the higher ups in

Montpelier strongly urged school systems across Vermont to

consolidate their schools, to provide better and more efficient

education. The superintendent's report in 1907 states that “It may

be necessary to combine schools during the coming year to meet the

requirements of new school law in regards to a legal school.”

The State of Vermont was the first

state in the nation to mandate publicly funded schools, in its 1777

Constitution. I had always thought that state taxation and funding

for schools was a recent development. Not true. In 1807, the state

of Vermont instituted a 1 cent property tax for education, that rose

to 3 cents in 1827. In the early 1900's, school systems got money

from the state to help with expenses for transportation and teacher

boarding expenses. The new requirements in 1907 denied this

assistance to schools that did not have an average attendance of six

pupils for at least 28 weeks. In 1908, one Barnard school did close,

and several others “caused anxiety”. This requirement coincided

with a statewide trend of loss of population in the hill towns. In

his report, the superintendent advised that Barnard's outlying

schools consolidate with the village school and form a graded school.

Graded schools were larger buildings that held multiple classrooms,

with one or two grades to a classroom, rather than a one-room

schoolhouse with all the grades taught by one teacher in one room,

thus the appellation “graded school” - or “grade school”.

In 1847, Vermont made school

attendance compulsory for children ages 8-14. Barnard took

compulsory attendance seriously in 1909. The town report lists

truancy notices for Jim Howard, Elbert Wood and F Roads, from the

town constable. That year, the town voted to purchase flag poles and

American flags for each school.

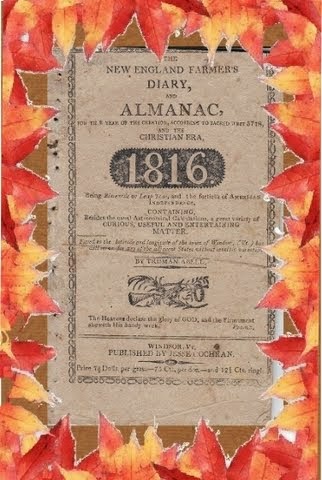

the 45 star American flag, 1909

The superintendent's report for that

year contains another pitch for consolidation. “It is harder to

give the children in the back districts equal advantage to children

in the village. It is difficult to get good teachers for those

schools. The cost per pupil is more, with less satisfactory

results.” That year, Barnard still managed to maintain 9 schools,

although only four had the same teacher for the whole year. Those

schools kept those same teachers for many years. Three schools had

only two teachers in 1909, but the rest of the schools switched

teachers after every term. The superintendent's assertion that it

was hard to get teachers for the schools outside of town is born out

by the statistics.

Alice Aikens, Seth's wife, taught in

one of Barnard's schools in 1906 and 1907. In the late 1800's, the

only qualification for teaching school was to have graduated from

high school. As the century changed, teachers qualified by passing

an examination. In one of the last town reports I read, the

superintendent said that it would soon be a requirement that teachers

have passed a teacher preparation course at an approved college.

The Aikens boys and their agemates in

Barnard were the last pupils to attend the one-room schools. In 1910,

Forrest joined his brother Francis in attending Whitcomb High School

in Bethel. In those days, attendance in high school was not

mandatory, but it was mandatory for school systems to pay tuition and

transportation costs for those who wanted and qualified to go. In

order to attend secondary school, students had to pass examinations

to qualify them for further education. A good percentage of the

students from Barnard did go on to attend high school.

For several years after Francis and

Forrest graduated from School 1 in Barnard, there is no school report

in the Barnard Town Reports. When the school reports show back up in

the town reports, Barnard has one school – the Village School in

the center of town, where Francis and Forrest went. My guess is that

there was such confusion around the consolidation that no reports

were written for those years. When the superintendent's reports

reappear, the Barnard School Superintendent is a woman, Mrs. A. C.

Thayer. Women had become eligible to be school superintendents in 1880

The arguments for increased consolidation of schools is still going on in the Upper Valley in the 21st Century. School systems like Hartford and Lebanon are combining student populations to decrease the number of schools in their towns. Small towns throughout the Upper Valley are considering regionalizing to save costs. Barnard School is one school that is the center of discussion. Are there enough students to continue running the school? The age-old question of transportation on snow-covered roads is still a concern. Students don't need to be home in the afternoon for farm chores, but families depend on the teenagers to watch the little kids while their parents work after school, which engenders discussion around transportation.

Most of the information used in this post came from the town reports of Barnard, available in the Barnard town offices. I also used information from The Vermont School Boards Association

"A Brief History of Vermont Public School Organization" by David Cyprian, 2012, and from

Two Vermonts, Geography and Identity, 1865-1910 Paul M Searles, 2006 Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England